Managing Excerptions: Reducing Choice

I started my blog to kick my non-writing habit. I've now got enough material to start blocking out a book (hooray!). So while I'm doing that, I thought I'd start a small series looking at some of the books that have influenced me

"Managing expectations" is one of my least favourite managerialisms. I cringe whenever I hear it. Expecting is about hope, which is the only thing that keeps many professionals going. We take what we can from life and do our best with it.

So this series is about some of the excerpts that caught my eye over the last six months. They're part of what gives me hope about the profession of management.

If I were to play management buzzword bingo with one phrase that no other player could take, I would take "evidence based". It's everywhere and if you work in the analytics sector (which I do) its become a ubiquitous article of faith.

There are all sorts of problems that plague this holy grail of management but that's for another series of posts. This post is about choice. Choice inevitably follows anything "evidence based". The logic flow is something like this: evidence leads to a decision and a decision is a form of choice.

When we decide to do something, we also decide not to do something else. Behind our decisions are our choices and if "evidence based" is a nest of vipers, choice is a den of dragons [There should be a rule in all business writing that 'dragons' be mentioned at least once].

Choice as an abstraction is something we think we'd like more of. But extended observation of management environments demonstrates that choice is something many of us avoid. The feel-good elements of 'having' choice conflict with the pure-dread elements of 'making' choice.

Barry Schwartz wrote 'the book' on choice in his 2004 work 'The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less'. The book focuses on the role of choice in the chronic unhappiness that afflicts our affluent world. But management professionals interested how the psychology of choice affects their decision making will find a lot of insight.

"The fact that some choice is good doesn't necessarily mean that more choice is better. There is a cost to having an overload of choice. As a culture, we are enamoured of freedom, self-determination, and variety, and we are reluctant to give up any of our options. But clinging tenaciously to all the choices available to us contributes to bad decisions, to anxiety, to stress and dissatisfaction."

I've named my little consultancy business from the word 'decisive', because of my view of the importance to management professionals of committing to one option. 'Being decisive' becomes about being ruthless with our "overload of choice". Schwartz,

"We make the most of our freedoms by learning to make good choices about the things that matter, while at the same time unburdening ourselves from too much concern about the things that don't".

This goes to the idea of materiality (roughly, what would make decision makers pause in their judgment) which, I'm sad to say, is a rare concept to many management teams. Knowing what matters and focusing blood and treasure on achieving what matters is the essence of strategy. Which is another management buzzword bingo winning word.

Shwartz gives us a handy little list of how to manage choice,

"We would be better off:

- if we embraced certain voluntary constraints on our freedom of choice, instead of rebelling against them. Seeking what was 'good enough' instead of seeking the best

- If we lowered our expectations about the results of decisions

- If the decisions we made were nonreversible

- If we paid less attention to what others around us are doing"

Next time you go through a decision exercise (that is, a choice making exercise) run yourself through this list. Bullet point four in particular is the one I recommend embracing. There is nothing like commitment to sharpen the mind.

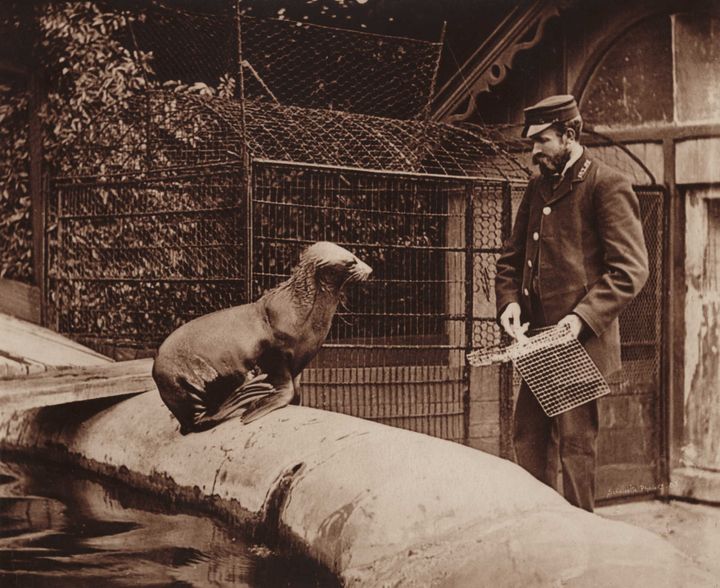

Image via Gratisography